I’m frustrated. I’ve finally received familial approval to cut the cord—something I’ve wanted to do for years. But I can’t make it happen.

With the exception of a few sporting events here and there, we haven’t actually watched television live or recorded on our aging TiVo in years. We’re a Roku and Plex household. In the back of our minds we’d kept cable service for when guests come and want to watch their favorite channels. That also hasn’t happened in years. It’s time to stop paying for something we don’t use.

In 2018, one would think that this is a simple transaction that can (and should) occur with a few clicks on a provider website. I can perform far more complex tasks online, so this simple exchange should be easy to support. And yet…

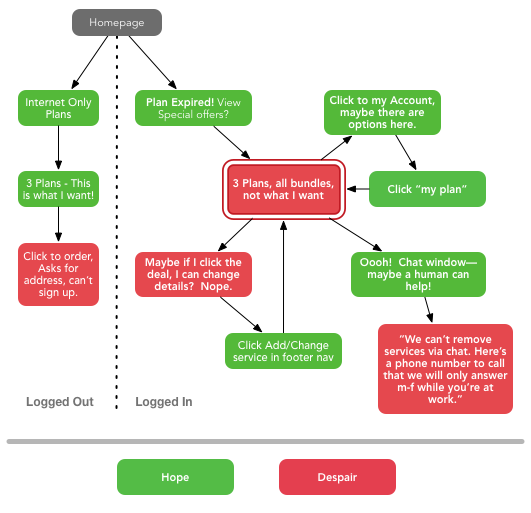

Here’s a rough CX path of my current provider’s website:

All paths lead to a single page if you’re an existing customer. When I get to that page, I’m presented with two offers: one for less and one for more money than I’m paying now. Oddly, they appear to be exactly the same package except that the less expensive one has higher internet speed.

That’s it. I’m given 3 options: stick with what I have or commit to one of these two alternate bundles. I could add things to my custom existing bundle, but I can’t remove video from the equation.

None of these is what I want. And a dark pattern is born.

Don’t trick me.

A dark pattern is any user experience that’s designed specifically to trick a user into doing something they otherwise wouldn’t.

Marketing often entails developing a customer experience or customer journey with the goal of convincing a potential customer to do something they may not have done otherwise.

The line between convince & trick is thin and slippery. Staying on the right side is the difference between a happy, trusting customer and a frustrated one.

We know that firms who elevate CX/UX functions to higher levels in the organization and who place the highest priority on creating optimal customer experiences are more successful. So why do these terrible experiences get created?

One possible reason could be cynicism.

So, here I am trying to cut the cord. There’s little if any value left for me in what my cable company has to offer. TV providers have long been struggling to grow and as broadband enabled streaming continues to eat away at their core business, the only model that seems to staunch the bleeding is to put up roadblocks to those trying to leave.

Enter friction.

As countless studies have shown, the more friction you have in a system, the more likely it is that a user will drop out of the flow. In this case, a customer who wants to cut the cord will reduce income for the company so dropping out of the conversion funnel could be seen by the organization as a lesser of two evils—perhaps even a win.

By making it as hard as possible to make this switch, I ended up paying almost 2 extra months for video service even though we weren’t watching it. Multiply that out by the number of people cutting the cord (assume I’m average) and then by the amount I spent over my new package (in my case $80) and you can see how it could make sense if the concern is short term income.

Convince Me.

If you look to the left of the vertical dotted line in the flow chart, you’ll see a very simple path to achieve my goal. It’s exactly what should also be on the right side of the line—a quick and easy way to succeed.

Worried about lost revenue? Get creative! You could easily upsell the customer before offering reduced service packages or develop adjacent services that truly add value.

The big benefit? Trust.

Who are customers more willing to trust, a company who throws up completely artificial roadblocks to keep us from reducing our service or one who prioritizes our needs and genuinely works to provide value?

AOL did the same thing during their death spiral. Is this kind dark pattern an indicator of corporate insecurity and impending demise?

It very well might be.

Leave a Reply